With Great Power is an RPG by Michael S. Miller that I’ve had on my shelf for a while. Flipping through it kindles bright “I want to run this” ideas. I planned for it to slot as a filler game for my home group (to buy time for other GMs to prepare prep-heavy games) and thought it would be fun to run at our monthly roleplaying meetup. With that in mind, I read, prepped, and printed references, and got ready to play.

With Great Power is an RPG by Michael S. Miller that I’ve had on my shelf for a while. Flipping through it kindles bright “I want to run this” ideas. I planned for it to slot as a filler game for my home group (to buy time for other GMs to prepare prep-heavy games) and thought it would be fun to run at our monthly roleplaying meetup. With that in mind, I read, prepped, and printed references, and got ready to play.

Update: When I first wrote this post, it looked like With Great Power was out of print. While you can’t find the print version, that’s because a Revised version of With Great Power is due in 2013. And now, back to the original post. –Scott

Game Structure

While this is an indie game, the roles are largely familiar. Players each create a character, while the GM keeps an eye on the overall story, devises the plot (with strong guidance from the book), and plays NPCs–the villains and minor characters that no one else picks up. So far it sounds pretty normal, right?

Actually, as far as locked down game mechanics, the game is pretty close to traditional lines. Where it deviates is in the text and advice, where Michael makes suggestions that might shake up your group’s norms a bit. You can drift it towards a traditional GM/player experience quite easily–but if you want to spread the load a bit, there’s solid advice to help. (In fact, a criticism of the game might be that it keeps in explicit view some of the things that we want to pretend are organic in a traditional story.)

Characters

In contrast to many super hero games, you spend little time thinking about the mechanics of your character’s powers. Much like Primetime Adventures, there isn’t a real “balance” between characters–you can run Dr. Manhattan in a game with the Comedian, or Batman and Superman in the same story, and not feel like the “mere mortal” should just head home and let the big boy do the work.

In contrast to many super hero games, you spend little time thinking about the mechanics of your character’s powers. Much like Primetime Adventures, there isn’t a real “balance” between characters–you can run Dr. Manhattan in a game with the Comedian, or Batman and Superman in the same story, and not feel like the “mere mortal” should just head home and let the big boy do the work.

The game requires group setting creation. “Super Hero Stories” is a very broad category; deciding on a specific tone or feel is important. Referencing specific comics, art styles, whether it’ll be street level or cosmic zap, is important to get everyone imagining the same comic. Now the group picks the struggle–what themes pull all of the characters, elements that all of the characters’ struggles reflect in some way. Examples include Responsibility vs. Personal Needs, or Justice vs. Vengeance. What’s important about this is that every hero needs to be torn between the two (thus, struggle), while villains pick one answer and take it to extremes.

Now that we know what the drama’s going to be, we make (or select) characters to match. Characters pick Aspects [not in the FATE RPG sense], the top 4-6 things that define their character. Aspects can include powers, origins, relationships, and motivations. Here are some things that are unique to WGP: Each Aspect has to align with one side of the struggle. (For example, your love interest might be part of your Responsibility or your Personal Needs. Where you slot him is pretty revealing, huh?) Each Aspect can be “damaged”–part of character creation is including an example of suffering for each Aspect. Very importantly–if you can’t provide an example of suffering, then that’s not an Aspect for the character this game. Finally, each character picks one of their aspects to be a strife aspect. Altering the strife aspect produces/requires more cards than normal aspects.

In play, affecting the story is abstract; you get as many resources in conflicts for imperiling “Aunt May” as “Spider Powers”.

Villains

Before the players ever show up, the GM can half-prepare their villains. These “proto-villains” hang out in a rogue’s gallery, waiting until a struggle is picked and players select strife aspects.

Once the strife aspects have been picked, the GM selects a proto-villain or two from his scratch pad. The villain then forms “The Plan”–an Aspect that explains how warping heroes’ strife aspects is essential to performing their grand task. The book has good advice about selecting a villain who fits the strife aspects, not trying to wrestle your favorite villain into pretzels to get them in a story they don’t fit.

An aside:

Interestingly, PCs and villains both have details that matter, but that aren’t Aspects. They remain “real” and can be used in descriptions–they just aren’t what the current story centers on. If “Spider Powers” is on your character sheet, a goal of the game is to kick those powers around and watch them suffer. If there’s no real conflict inherent in them–they work, no fuss, no debate required–then they won’t be a part of the struggle. Other aspects have to step up and take the role.

So we’ve got heroes and villains, and the villains have a plan. Now what?

Play

There are two types of scenes: Enrichment and Conflict. The GM selects a player, who picks the type of scene, what characters are present, and what they’re up to.

Enrichment scenes are moments in a character’s life touched by the struggle. During an enrichment scene, players select an Aspect to highlight. So a scene about a character’s relationship with their grandma could involve a visit to the nursing home, a talk with her doctor, or searching for a clue to where the villain has taken her. One of the options recommended in the text is to have other players, rather than the GM, play your NPCs (after a brief, “their motivation is X” direction). While it’s not a radical idea, it’s integrated in the book in a way that strongly encourages it, rather than as just an aside. Early in the game, enrichment scenes introduce the elements of your character’s story–we meet Aunt May, we see Wolverine’s claws rend a bot in training. The game uses story structure–Aspects are introduced like Checkov’s gun; primed Aspects can be used in later Conflict scenes.

After each character (including the villains) has a few enrichment scenes, someone will pick a fight. That’s conflict! Resolving conflicts is much more involved than an enrichment scene; the card play is similar, but there are several exchanges, not just one card comparison. (For an illustrated example, see this illustrated excerpt from the book.)

After a conflict, the participants will usually be pretty wiped out and need to recharge and regroup. So they’ll take some enrichment scenes to repair some of the damage to their Aspects, and rebuild their hand by showing how other parts of their life slide as a consequence of their superhero activities. It’s a self-driving cycle. Of course, if you don’t need to recharge, you can always leap directly into another conflict…

What’s Different?

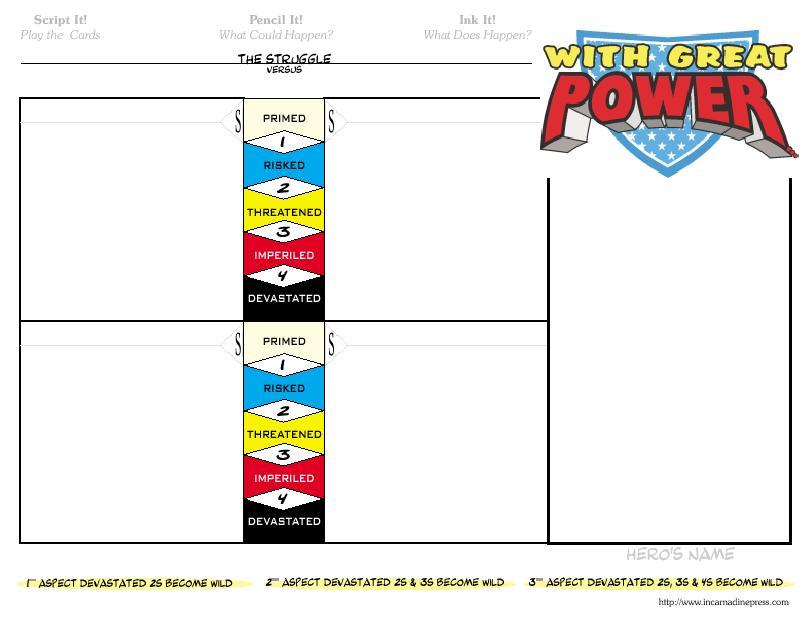

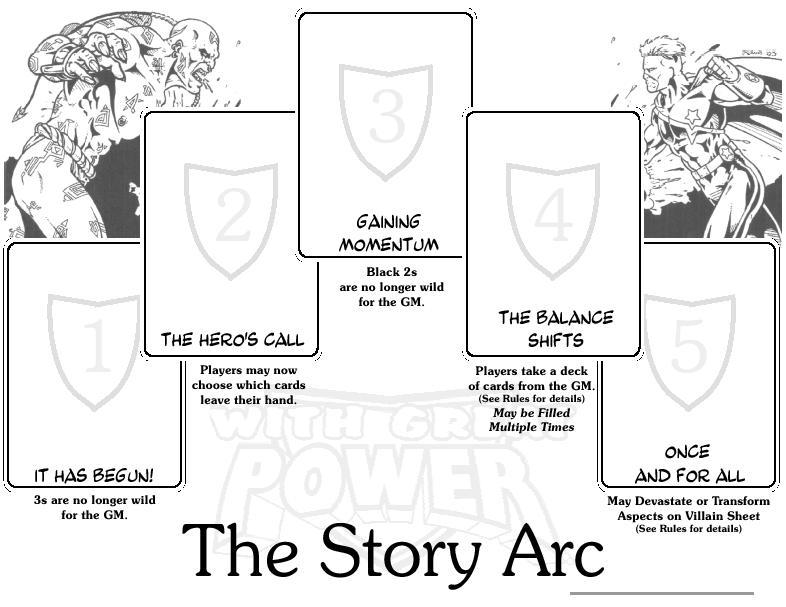

Game Structure: The Story Arc–At the beginning of the game, the rules are stacked in favor of the GM, who tends win the early conflicts. But–as a PC, losing a conflict allows you to advance the story arc, which changes the rules in the PCs’ favor. It’s a slick way to reward players when their characters lose a battle. It builds the game’s plot like a novel or comic–early setbacks reveal the true mettle of the heroes, who struggle on and come back loaded for bear.

Game Structure: The Story Arc–At the beginning of the game, the rules are stacked in favor of the GM, who tends win the early conflicts. But–as a PC, losing a conflict allows you to advance the story arc, which changes the rules in the PCs’ favor. It’s a slick way to reward players when their characters lose a battle. It builds the game’s plot like a novel or comic–early setbacks reveal the true mettle of the heroes, who struggle on and come back loaded for bear.

The story arc doesn’t define a fixed number of scenes for the game, but it does mean that the PCs have to lose some conflicts to unlock “Once and For All”, allowing the story to end. This structure has elements in common with the GM’s Turn/Player’s Turn of Mouse Guard.

Ability measured by Story Impact–Characters gain cards (used to win conflicts) for changes to their Aspects. They improve their odds of winning based on how dramatically their character has been affected by the story, not by devising clever tactics or using powers the right way.

Player Resources–Players use their hand of cards to win fights–and can intentionally lose enrichment (or even conflict) scenes to keep their hand strong. Managing a hand of cards, and picking what cards you’ll retain, has a different feel from random die rolls and card flips (like PTA).

Adventure Design–Players select the Aspects that they want the story to revolve around by indicating one as their strife aspect. The GM takes that player input, and builds (or completes) villains who have a crazy plan to [do something] to [the Aspect the player picked], twisting it to take over the world!

Any Questions? Any Answers?

Have you had a chance to play With Great Power yet? I’ve prepped it, but haven’t had a chance to watch it all go sideways when we fumble with it at the table. If you’ve played it, I’d love to hear about how it played out for your group. Whether you’ve played it or not, if you’re interested in any aspect of the game, ask away!

I’m positive I played this at Origins a few years ago. Maybe 2007? It’s long enough ago that my memory is a bit fuzzy on it. I remember it having some interesting ideas built into the game, but the execution having some problems. I think you nailed it when you said “a criticism of the game might be that it keeps in explicit view some of the things that we want to pretend are organic”.

I really enjoyed the way the characters and their motivations (struggles) were set up, but the game seemed to stop and start too much. Rather than letting the scenes evolve naturally from one part to another, things would just get going in one scene only to stop and shift to something else. The GM was most definitely NOT railroading us, but the movement from scene to scene felt a little forced.

All in all, I was glad I got to try a unique game like this at a con, but it wasn’t something I would seek out to play again. Of course, anyone who GMs might be interested in checking it out for the game theory in it.

Now that I have read the article…. Where can I find this? The incarnadine website has bad indie press revolution links, and the IPR site doesn’t find anything from a search for WGP.

I really like Primetime Adventures, and this sounds like an long lost relative.

@Orikes – Thanks for the forewarning! In reading through the forum threads, it was clear that some tweaks continued after publications–like leading with color first in setup. Some of the successes–in particular the Nightwatch game–make me think that a skilled group could have a very enjoyable game, even if some of the skeleton is visible.

@lomythica – I didn’t realize until I’d read through the book a second time and was digging through forum threads, that the designer has moved on from game design and support. (His about me page now reads: “The vast majority of my internet presence is centered around role-playing games. I used to publish games at Incarnadine Press, but I don’t any more.”) I suggest writing to him directly–his current blog is http://stalwart1000.wordpress.com/ . Sorry for getting up you interest and making it so hard to fulfill!

This looks like a game that could really deliver on its home turf – the resolution of internal conflicts. (I find it interesting and downright obvious that the example is ‘spider powers’.)

But it also looks like one that could go horribly awry when the players aren’t all playing the same game, as it were. I’d really like to see this in action, and see if the internal conflict resolution mechanics (or concepts) are driftable. My Monster Hunter game could benefit from a good “what we’re fighting for” discussion/argument.

That seems very interesting Scott. Consider me sold on trying it out either at the Fresno RPG Meetup or with our own group at some point.

Here was my progression:

Wow, this sounds really cool!

Ooh, I love the proto-villains and the story arc mechanic. This sounds like a supers RPG in a different vein.

Okay, I wonder if it’s cheap enough to snag.

Wait, it’s no longer for sale anywhere, even in PDF?

🙁

Thanks for the great review, Scott. You really nailed it when you said “Managing a hand of cards, and picking what cards you’ll retain, has a different feel from random die rolls and card flips.” It’s one of my favorite parts of the game.

I hope your game goes well. If I can help, let me know.

As for the game’s availability, my game publishing was on hiatus for all of 2011, but I’m starting to look into revising With Great Power rather heavily. Anyone interested in a PDF copy should contact me directly.

@Kurt “Telas” Schneider – Spider powers was my example, inspired by some comment threads. The book creates its own characters and follows them through; The Stalwart, and his Armor of Truth, provide a great example for a different Struggle.

One thing I didn’t touch on is the thought bubble–it sounds cheesy, but seems like an excellent way to express thoughts inside a character’s head at the table. I was going to have my players create their own thought bubbles (on a 4×6 card)–dark boxes, Snoopy’s bubbles, or anything else.

@BryanB – Yay!

@Martin Ralya – I’m glad that Michael showed up to provide lomythica and you a chance to read it for yourselves.

@Michael Miller – Thanks for following up. I hope that the interest continues to lure you back to design’s dark side. I liked many of the proposed ideas mentioned in later threads–like the villain focused conflict sheets. I look forward to a revised edition!