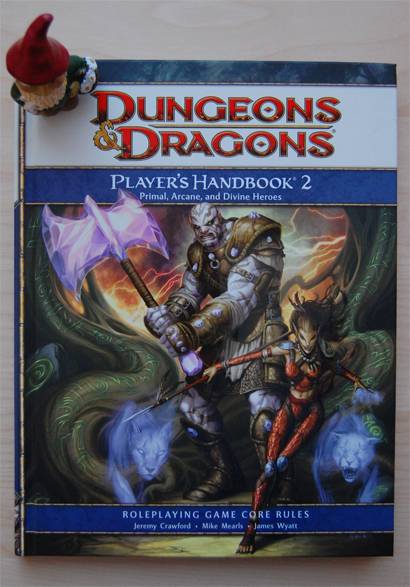

A couple of weeks ago, Wizards of the Coast offered Gnome Stew — and several other RPG blogs — the chance to write an article about the Player’s Handbook 2 in exchange for a pre-release copy of the book. Specifically, an article about the book from a GMing perspective. We jumped at that chance.

I’ve been poring over the PHB 2 since early March — reading, taking notes, and asking Gnome Stew readers (here on the Stew, via email, and on Facebook) what they, as GMs, want to know about the PHB 2. At 4,500 words, this in-depth overview of the PHB 2 from a GM’s point of view is the result.

Want to see what the PHB 2 looks like to a veteran GM — and how it will impact your campaign — four days before it appears in stores? You’ve come to the right place.

A bit of background: I looked at the PHB 2 purely from a GMing perspective. I’ve been running and playing D&D for 20 years, I’ve played (though not yet GMed) 4e, and I’ve written over 700 articles for GMs, both here on the Stew and on Treasure Tables.

So far, I love 4th Edition; it does the things I like most about D&D exceptionally well. You can read my launch day review of the core books or my take on the Forgotten Realms Campaign Guide to see where I’m coming from.

This article isn’t a review, although it includes review elements, and I won’t be getting too crunchy with the individual classes — other (excellent!) RPG blogs are handling those topics today. Links to all of them appear at the end of this article.

Sound good? Let’s rock.

The Meat: Eight New Classes

Classes are what the PHB 2 is all about — everything else is ancillary, or supports the classes. That makes the PHB 2 a simple, pure, and polished book. This is one of the things I’ve enjoyed about 4e products to date: they pick one thing, do it very well, and don’t try to do much else.

If you or your players pick up the PHB 2, it will be for the classes.

The PHB 2 demonstrates the strength of the role system. Before I dive into the classes themselves, let’s talk roles for a moment. I was originally pretty neutral on the role concept. I could see the value for building a balanced party, but I didn’t think it was a system I’d give much thought to down the road. Enter the PHB 2 — with this book, the role system really shines.

For one thing, there are now 16 core classes, plus some variations (the ones found in Martial Power, and soon more in Arcane Power — and beyond) and campaign-specific classes (from the Forgotten Realms). By flagging each class with a role, it’s easy to break them down in terms of what you want to play.

And without a role designation, it wouldn’t be immediately obvious what some of the new classes are like. Quick, what’s an invoker do in combat? Or a bard? (And no, unlike previous editions the answer to that question for bards is not “Die horribly, while singing.”) Knowing their roles (controller and leader, respectively) gives you an idea of what they’ll be like to play, and it’s quite handy for new and old players alike.

Now that there are 16 role/class/power source combinations to consider, I find roles to be an essential tool for understanding — and getting the most out of — 4th Edition.

The classes: more solid options for everyone. There are eight new classes in the PHB, a mix of entirely new ones and re-imagined classes that have appeared in previous editions. Along with their roles and power sources, they are:

- Avenger, a striker (divine)

- Barbarian, a striker (primal)

- Bard, a leader (arcane)

- Druid, a controller (primal)

- Invoker, a controller (divine)

- Shaman, a leader (primal)

- Sorcerer, a striker (arcane)

- Warden, a defender (primal)

Let’s recap the original PHB’s breakdown the same way:

- Cleric, a leader (divine)

- Fighter, a defender (martial)

- Paladin, a defender (divine)

- Ranger, a striker (martial)

- Rogue, a striker (martial)

- Warlock, a striker (arcane)

- Warlord, a leader (martial)

- Wizard, a controller (arcane)

Because the PHB 2 is part of the core book line for 4e, for the purposes of this article I’m going to set aside the classes from the Forgotten Realms Player’s Guide. Not every GM will be running a Realms campaign, but nearly every GM is likely to consider the books in the core line, like the PHB 2.

Seeing the 16 classes broken down like this brings a few things to mind from a GMing perspective. For starters, there are now three controllers, three defenders, four leaders, and six strikers to play. Particularly for players who liked the wizard but wanted more controller options, this is a good thing.

Notice the lack of overlap, too: Out of 16 classes, only two pairs share the same role/power source combination — the original PHB’s ranger and rogue, and the warlock and sorcerer. Now think about how different the rogue and ranger are from each other in nearly every sense — to me, they’re totally different animals (and the same goes for the warlock and sorcerer).

Similarly, if all I’d heard about the avenger was that it was a holy warrior class, I’d think, “Why do we need another paladin?” — but knowing that while they share a power source (divine), the avenger is a striker and the paladin is a defender makes a huge difference. That difference shows through once you drill down to their powers, too.

So what does it say about the PHB 2 that with eight new classes, there’s zero new overlap? Bingo: the eight new classes weren’t just phoned in — they’re fully realized classes in their own right, not just variations on old themes.

And just as classes that shared a role in the original PHB were pretty interchangeable in terms of creating a balanced, fun, and playable party, so are the new ones. You can mix and match within roles without mucking up the basic formula for a balanced D&D party (one class of each role) — but classes that share a role are different in more than enough ways to dramatically change how the game actually plays out depending on which class you choose.

For me, that’s a great approach: All the fun of variations in player and PC roles with none of the heartache that would come with, say, all strikers not being created equal.

The new classes will quickly become a part of D&D lore. Every edition of D&D has shaken up the class mix, but this is the first edition to have so many classes so soon. Between the PHB and the PHB 2, there’s something here for damned near everyone.

Players familiar with 3.x already know the nuts and bolts of the barbarian, druid, bard, and sorcerer (although they’re in for surprises, too: these classes have changed dramatically, just like the first eight core classes did) — but the four new classes are just that: new.

The four new classes are differentiated from the 12 familiar ones in every sense — concept, role, power source, and of course their specific powers — and they put a new spin on D&D. Having a class like the shaman (a leader who assists his party in tandem with his spirit companion, and whose player will have to look at the battlefield in an entirely new way) in D&D represents a departure from standard fantasy fare — and I think it’s a good departure.

Remember how you felt when you first cracked open the 3rd Edition PHB and read the sorcerer? And remember how quickly sorcerers became a staple of D&D, and then a part of the game’s lore? The avenger, invoker, shaman, and warden will become a part of D&D lore, just like the sorcerer did when 3rd Edition was released.

There are subtle — but real — distinctions between all 16 classes. One thing I’ve consistently heard about 4e is that mechanically, the classes are all pretty similar. And I see that perspective: Fundamentally, a lot of powers from different classes work in more or less the same way, just with slight variations.

But with 800 new powers added to the existing 800 (more, if you include Martial Power and other sources), as a GM I’ve observed that the distinctions between classes can be subtle, but they’re there — and they become more dramatic and obvious once the dice hit the table.

For example: The shaman is a leader with healing and buffing powers. Sounds like a cleric, right? Yes and no. Unlike the cleric, many of the shaman’s powers stem from and revolve around her spirit companion: PCs and enemies adjacent to the spirit can be affected, and the shaman herself can also do things directly.

That puts a very different spin on a similar kind of class. A player running a shaman PC has to think about two characters every round, and consider positioning and movement more carefully than someone running a cleric. Their power sources (primal for the shaman, divine for the cleric) add another layer of differentiation.

For me, this is the crowning achievement of the PHB 2: WotC has added eight classes and 800 powers to the game, and not only do they not feel tacked on, repetitive, poorly thought out, or otherwise troublesome in any way, all eight new classes are worthy — and fun — additions to D&D.

None of the classes suck. This is one of the best features of this book for me as a GM: there’s no cruft — not a single bad class. Just like when I first read through the original 4e PHB, I can see playing and enjoying every class in the PHB 2.

Even the bard — formerly the poster child for classes that rarely get to do anything useful in combat or dungeon crawls (D&D’s core activities) — is full of interesting options, and is every bit as viable as the other classes.

The reason I dig that as a GM — and the reason you, as a GM, will dig it too — is that it removes a major worry from consideration when starting up a new campaign. You can let your players use any of the 16 classes currently available without worrying that someone is unintentionally getting screwed in the process.

They also seem balanced. Actual play is the only way to be sure, but based on my read-through, there are no balance issues here. All eight classes are evenly matched, and stack up well both against each other and against the original eight.

Hiccups might be uncovered down the road, as the PHB 2 filters into groups and onto gaming tables, but I can say with confidence that no glaring balance issues jumped out at me — and I’m a balance nazi.

New variations, not a fundamentally new approach. It’s worth noting that just like the original PHB classes, the PHB 2 classes are all about combat. As in the core rules, non-combat “powers” are almost exclusively rituals.

Whether you loved or hated that aspect of the original PHB, the PHB 2 isn’t going to change how you feel — it alters the game by introducing new and fun class options, not other new elements. Even the backgrounds (covered later) don’t mess with 4e’s basic formula too much.

The PHB 2 isn’t a book that sets out to change how you think about D&D, it’s a book that sets out to give you and your players more ways to have fun with the core elements of 4th Edition — adventuring, exciting combats, dungeon crawling, and loot. I like 4e for what it is, so for me this is a good thing; I find the simplicity of the PHB 2 refreshing.

Good classes for new players. 4th Edition turned an old D&D truism on its head: In previous editions, you gave a new player a fighter. Once a round, you hit something; in between, try not to die — pretty simple. And you avoided giving them the wizard, who had scads of spells to review, weigh against one another, and keep track of every single session.

In 4e, the opposite is true: In many ways, playing a defender (like the fighter) requires more tactical acumen and complex considerations during combat than playing a controller (like the wizard). Very generally, I would put strikers in a similar boat: good for new players.

So of the new PHB 2 classes, I recommend the avenger, druid, invoker, and sorcerer for players who are new to 4th Edition, or new to gaming in general.

Some classes are less suitable for new players. Leaders are a bit like defenders: When you play a leader, you have to think about every other PC on the battlefield, not just your own character — because so many of your powers revolve around other characters. That can make them a bit harder for new players to grok.

On this basis, I’d say the barbarian, bard, shaman, and warden are less suitable for new players.

Why the barbarian? Because despite having some of the striker’s essential simplicity, the barbarian’s rage mechanic — which is similar to a fighter’s stances, and has powers that stem from it — adds a layer of complexity.

That said, one thing I dig about 4e is that because of how it breaks rules up into little pieces — each character’s powers — any class, including the eight in the PHB 2, will be reasonably easy for a new player to pick up and enjoy right out of the gate. Even the ones I’d argue are better suited to players with more experience aren’t poor choices for new players.

How will the new classes change your game? Because 4e gives players (and GMs) an incentive to form a fairly balanced party — or at least to carefully consider an imbalanced one (there’s nothing wrong with a four-striker group, it’ll just make for a VERY different campaign) — the new classes don’t force any major changes in how you run your game.

Sure, there are now more options for each role, but even before the PHB 2 you could wind up with a party with two defenders, two leaders, and nothing else. That hasn’t changed; it’s just that now your players have more options in every role.

This isn’t to say that a D&D campaign with a shaman PC in it won’t be different from a campaign that only uses the classes from the original PHB — it will be different. You’ll run different kinds of adventures, introduce roleplaying elements specific to the shaman, adjust the tone of the game to match a party that features a primal PC, etc. — but the PHB 2 doesn’t introduced any foundational changes to the system itself, or to what makes 4e the game that it is.

New micro-rules, not new rules. One of the things I love about 4e’s approach to class powers is that despite having 100 (or more) for each class, you only have to keep track of a handful of them at any one time.

And everything you need (with a few exceptions) is right in the power’s description — or better yet, on a power card. This includes new rules related to each class, which makes learning the game considerably easier for players and GMs alike.

By and large, the powers in the PHB 2 (and the original PHB, for that matter) don’t introduce many full-fledged new rules — they introduce micro-rules. To pick one example out of hundreds, let’s peek at the druid’s 1st-level Flame Seed at-will power.

If it hits, Flame Seed creates a zone of fire around the target; until the end of your next turn, enemies entering those squares take damage. That’s not a new rule, it’s a micro-rule: a small mechanical element that’s easy to keep track of — and best of all for GMs, one that the druid’s player can happily and easily keep track of on his own. Instead of a rule in the combat section that explains how a one-turn zone of fire works, all the info is built into the power itself.

With each power carrying a tiny rules payload, the PHB 2 avoids introducing new core rules, substantial new mechanics, and even little things that add up, like new conditions — there aren’t any of those, either — into the game as a whole.

There’s only one thing in the PHB 2 that every player and GM needs to think about, remember, or add to their mental store of game rules and exceptions — the Rules Updates appendix, covered later in this article.

Here’s why that’s important: You can add the PHB 2 to your campaign without worrying about plumping up 4e’s game system with new crunch.

That’s significant for me because it means that as a GM, I don’t have to carefully vet a bunch of optional rules, new mechanics, and other changes to the game. The PHB 2 introduces new classes and support material for those classes — that’s it. I like that approach.

Dude, I want to make a [PHB 2 class] now. The PHB 2 is a supplement, and like all supplements — particularly for D&D — it will likely prompt at least some of your players to start thinking, “Hmm, I’d really rather be playing one of these classes…” My take? That’s just fine. (And it’s inevitable, unless you only play games after they go out of print.)

At the end of the day, what’s more important: The campaign plans you’ve made around the current party (which will change if a new PC is introduced, creating more work for you), or your players having fun? Right — the second one.

If one of your players wants to start from scratch with a new PC because she just picked up the PHB 2, let her. Work together to incorporate the new PC into the campaign, come up with compelling reasons for the old PC’s departure and the new character’s arrival, and generally collaborate to make the process as smooth as possible.

Personally, I haven’t found this to be a huge problem in my campaigns. If a player isn’t sufficiently invested in his current PC, then something is already wrong — and a fresh start might be just the fix he needs. Similarly, a player who loves her current character isn’t likely to roll up a new one just because more classes become available.

Do you, as a GM, need this book? Yep. The classes in the PHB 2 are so strong that I actually put this book in a different category than most D&D supplements (from this or previous editions): it’s not really a supplement, it’s an extension of the core book.

Every class might not be appropriate to your campaign, and therefore might not be essential to you — but enough of them will be appropriate, and because of the importance of classes in 4e, that makes them essential. Even just looking at two elements — the primal power source and the two new controllers — there’s enough here to make the PHB 2 “required reading.”

Unlike the PHB II for 3rd Edition, which was kind of meh overall, and definitely not essential, the 4th Edition PHB 2 feels like the 200+ pages that didn’t make it into the original PHB for space considerations — I consider it a core book.

New Races

There are five playable races in the PHB 2: one new one, the deva (former immortals with connections to their past lives), and four re-imagined ones — gnomes, goliaths, half-orcs, and shifters.

Will your players dig them? On the whole, yes. The deva are a cool concept, and the other four races are all welcome additions to 4e. They all offer good roleplaying hooks, and only the deva and goliaths might not fit into the “average” fantasy setting.

They seem slightly weaker than the core races. My gut instinct is that the PHB 2 races are slightly weaker overall than the races in the PHB. The deva are a good example. They get the standard +2/+2, 6-square speed, and +2 to two skills, and their goodies are: one extra language, +1 against attacks by bloodied creatures, necrotic and radiant damage resistance, the “immortal” creature origin, and an encounter power that adds +1d6 to the result of a die roll.

In terms of raw power, I’d take any race from the original PHB over the deva, unless their stat bumps (Int and Wis) were just perfect for my class of choice — but the gap isn’t huge. Still, for a supplement to offer up something slightly weaker than a core book is unusual; power creep is more the norm. (We’ll be coming back to power creep.)

There is one big problem, though… And I think we can all agree on what it is:

On the right there is a gnome; the thing on the top and the one on the left are…kender who’ve been infected with the black oil creature from the X-Files? Norfin trolls? Or (as one of my fellow gnomes put it) anime hairdressers, maybe? BAD MOVE, WIZARDS.

Ahem.

Moving on.

Character Options

This is the support chapter — goodies for the aforementioned classes, and a few for other classes, too. It includes backgrounds, feats, gear, magic items, and rituals.

Backgrounds are a great idea, but… If you have any players in your group who are relatively new to roleplaying, the PHB 2’s backgrounds will come in very handy for them. For experienced players, they’re nothing new — but as a GM, I do like them as a sort of shorthand for sketching out a character.

Backgrounds — in the mechanical sense that the term is used in the PHB 2, not the more general one (IE, a PC’s backstory) — give your players cues about their characters. They can be used to define a new PC, or to fill out gaps during character creation. They’d also be pretty simple to implement in an ongoing campaign, as they can be easily applied to existing PCs.

They’re broken down into categories — geography, society, birth, etc. — with multiple ideas in each category. “Occupation,” for example, includes artisan, criminal, entertainer, farmer, and so forth. Once you’ve chosen your elements, you get one minor mechanical benefit (like +2 to a skill). The book suggests choosing one concept from each of three different categories; again, for a new player that’s a great way to get started.

So why the “But…”? Because the mechanical element seems flawed — and like the races, it’s weaker than the version presented in a previous book. In this case, that book is the Forgotten Realms Player’s Guide, which features regional benefits — minor mechanical bonuses granted to PCs based on their home region.

The regional benefits presented in the FRCS are categorically more powerful than the ones in the PHB 2. In fact, they usually combine two of the PHB 2’s background benefits. And again, that’s weird: it’s the opposite of power creep, and a bit surprising for a supplement.

So…there’s no power creep? Right — zero power creep that I saw. Adventurer’s Vault and Martial Power both introduced a bit of power creep, and honestly I half expected to find some in the PHB 2.

As with class balance, actual play is the only way to really compare the classes, powers, and other elements of the PHB 2 to their previously-published counterparts. But my power creep radar never went off while reading this book, and the only power changes I could find — in the new races and the background rules — went in the other direction: slightly weaker than their predecessors.

Feats, magic items, and rituals are mostly self-contained. The vast majority of the feats in the PHB 2 are specific to the classes presented in this book, with a good spread of feats for each class. There are a handful that can see wider use, though, so if you have a PHB 2 available during character creation, your players will probably want to glance at it no matter what classes they’re playing.

Ditto with the new magic items: most of them are geared towards the classes in this book, although there is a good amount of spillover into general-use items.

The new rituals are a more even mix of general-use and PHB 2 class-specific — many of them are for bards only. Between the bard-specific mundane gear (instruments), magic items, and rituals, there’s quite a bit of support for bards — which is right in line with how much better that class is than previous incarnations.

Appendix: Rules Updates

To close things out, both in the PHB 2 and in this article, we have the Rules Updates appendix.

I cringed, then I relaxed. When I flipped to this section for the first time, my reaction was, “Oh, shit, a bunch of stuff has changed already” — but that wasn’t borne out once I started reading. Heck, the whole section is only 5 1/2 pages long.

The majority of the appendix is given over to a new version of the “How to Read a Power” section from the original PHB; the new version replaces the original text. It incorporates clarifications and new PHB 2-related stuff, and again: nothing major.

That’s followed by an overview of all of the power keywords — from power sources and damage types to effect types — published to date in the PHB, Martial Power, and the PHB 2. And last but not least, the Stealth skill has changed somewhat, and the Buff and Perception skills have been updated to match those changes.

This appendix covers fairly small stuff, but it represents an important update to the core rules. I’d say every 4e GM should at least glance at this section, and most will likely want to use it as written. I also don’t feel that these pages took space away from any of the other, more interesting, sections of the PHB 2 — I’m glad it’s here.

Closing Thoughts

This is a good book. In the PHB 2’s intro, WotC calls it “the most significant expansion yet to the 4th Edition Dungeons & Dragons game,” and I agree. What makes it significant is the fact that it introduces a mix of revamped favorite classes (and races) and entirely new ones, and does so without any of the problems common to supplements — no shitty classes, no power creep, no balance issues, and no unfortunate mix of useful and useless material.

The new classes look like a lot of fun. Like I said, I can see trying any of the PHB 2 classes and having a good time with them. (I’m working on a D&D character right now — a dwarven fighter — and I’ve seriously considered scrapping him in favor of a wild magic sorcerer…) The avenger, warden, invoker, and shaman, in addition to being cool in their own right, are going to become a part of the lore of D&D — just like the sorcerer did in 3rd Edition.

Acknowledgments

My thanks to everyone who asked questions and offered up topic suggestions for this article: Lesink, Rafe, Sarlax, Monoxide, ZenCorners, BarMP, Swordgleam, CoolCyclone2000, and DocRyder (all right here on the Stew); Rustin Simons, Juan López, and Tristan Tarwater (on Facebook); Ron Brown Jr. via email; and of course my fellow gnomes. I wasn’t able to cover every question, but all of your input was appreciated — and made this a better article.

And a big thank you to Wizards for giving us this opportunity. We’ve never had a preview article like this on the Stew before, and writing it was a lot of fun.

Questions?

I’ll be happy to field questions in the comments. Thanks for reading this beast, and I hope I’ve helped you decide how the PHB 2 will fit into your campaign.

More Pre-Release Info on the PHB 2

Want to learn more about Player’s Handbook 2? Read on…

- Atomic Array: Episode 018: Player’s Handbook 2

- Game Cryer: Player’s Handbook 2 Review

- Gnome Stew: A Veteran GM’s Take on GMing and the PHB2

- Critical Hits: The Avenger

- Campaign Mastery: The Barbarian

- Uncle Bear: The Bard

- Critical Ankle Bites: The Druid

- Kobold Quarterly: Review: Player’s Handbook 2

- The Core Mechanic: The Invoker

- Flames Rising: The Shaman

- Stupid Ranger: The Sorcerer

- Musings of the Chatty DM: The Warden

Drop by Wizards of the Coast today!

Martin, the only nit I can find to pick is your take on the “new” classes and how they will quickly find a place in DnD lore etc…

Not having the book yet I can’t say for certain, but all the names have been in DnD before, some of them as long ago as the pre-hardback folio edditions, and the old concepts linked to those names appear to match well with the roles/powersets you’ve noted.

I could be falling prey to “it’s older than you think” syndrome, but here’s the earliest I know of each of them appearing:

Avenger – by far the oldest, back in the days of Basic DnD, you could “multiclass” a bit once you hit name level. A lawfully aligned figter could become a Paladin, a neutrally aligned one could become a knight, and a chaotic one could become an Avenger. I seem to remember them being in early printings of 1e and the early folio edditions as well but that’s a bit fuzzy. Avengers were bad guy whoop-ass versions of paladins.

Invoker – was a 3e prestige class centered on making your Summoning spells more powerful and varied.

Shaman – Was a set of 2e kits for the cleric class in the complete book of barbarians. Also, represented in 3e in the Oriental Adventures book. Both were spirit-centered holy men/warriors.

Warden – Was a kit for druids in 2e devoted to protection of the forest, etc… Pretty much your default druid but more defense oriented. It seems like the most liberty has been taken with this concept.

Anyone verify contest any of these?

Martin, are the concepts behind the classes more or less true to previous material, or do some or all of them break new ground?

Um. Warlock and Sorcerer also share a role and power source.

Sorcerers are supposed to be striker (primal)?

@Matthew J. Neagley – Sorcerers are Arcane, for certain. This much is listed in WOTC’s preview on the DDI web site.

If they were Primal, then there would still be overlap with the Barbarian.

There is nothing wrong with role/power source overlap. I was just pointing out an inaccuracy in the article.

Excellent article, Martin! Especially with a newborn in the house; all I got to read was “What To Dread When You’re Expecting” books.

No power creep, huh? I guess WotC laid of the group in charge of power creep. (I believe they were “addictive marketing” specialists hired from the tobacco companies.)

I’m sure it will pop up somewhere, but how did the preview version of the Barbarian match up with the final version? This may point to WotC’s accuracy in future class/race previews.

Finally, this old grognard thinks that the whole anime/cartoon style of art that is popular in RPGs right now can simply go to hell. Swords are thin and light, or you wouldn’t be able to swing them. The visible part of the eye is not bigger than the mouth. Armor is functional first, decorative second, and does not protect the off-hand side better than the weapon-hand side, especially if you’re not carrying a shield. Hair is not …whatever the hell it is in these pictures, tentacles? And don’t even get this old Infantry soldier started on the lack of rucksacks/backpacks. Where do they carry all their stuff?

Sheesh, I’ve got a whole rant/article right there…

Thanks for the excellent review, Martin. I’ve been really hesitant on the PHB2, but this may just find a home in my bookshelf.

I’ve never gotten to play 4e, but I’ve wanted to try it (controversy dictates that I must give it a chance instead of blindly scoffing). I’m actually afraid that I’ll really enjoy it.

Now I have bards that rock. I can’t afford new hardbacks.

Great review — you just made up my mind to buy the thing. Anyway, here’s a thought: now that all but the martial power source offers all four character roles, that system can be easily leveraged to facilitate the creation of parties that make sense in combat and by whatever story is being told.

For example, I am anxiously awaiting the release of the Eberron CS — that’s my world, that’s where we like to play. I’ve run campaigns in the past that were made up of members of the Church of the Silver Flame. I suppose that now I could have a balanced party, per roles, in which all PCs draw their power from the divine source. That then makes weaving a group story together far easier. Sure, the Church has goons who’d use the martial source; but wouldn’t it be cooler to use an avenger, invoker, paladin, and cleric? All of the Church, all powered by their divine association? Ditto for a primal party. The only thing we’re lacking now is a martial controller, which is no big deal.

So I’ll buy this book, partially for that story-rules-roles convergence. Very cool, indeed.

@lyle.spade –

Oh I’m stupid…no arcane defender, either…yet? So divine and primal power sources are represented in all roles thus far.

@lyle.spade – If you’re willing to use a “non-Core” book, the FRCS has the Swordmage. It’s a pretty amazing arcane defender, and one of my favorite classes so far.

@Throst

I’ve tried to like FR, but I don’t. I had the 3e CS, and it sat on my shelf for years. I bought toe 4e FRCS, looking for a fresh start, and was bored by it, too. Unless the swordmage fits really well into Eberron, I’ll probably not use it at all.

But thanks for pointing that out — only the martial source now lacks a controller.

Great stuff! Thanks, Martin!

@Matthew J. Neagley – Those are good nits — your D&D knowledge is much more encyclopedic than mine. I don’t consider prestige classes, kits, and other pseudo- or semi-classes to be actual core classes, though — for my money, these are new. I think they’ll be new for many players and GMs, too.

@Throst – Good catch! See what having a new baby does to your brain? 😉 I’ve corrected that section of the article.

@Kurt “Telas” Schneider – I’m glad you enjoyed it, Telas. Honestly, I have no idea how the preview barbarian stacks up to the one in the PHB 2; I’ve never seen the preview.

@lyle.spade – Very good point — I hadn’t considered that at all. As for arcane defenders, the swordmage isn’t really tied to the Realms, and it’d be easy to use in just about any D&D setting (Eberron included).

@Rafe – Thanks, Rafe! This took forever, but it was totally worth it. I’m a zombie today, though. 😉

@lyle.spade – Lyle, I bought the FRPG just to get the complete Swordmage, and I can attest that the class can (and will, once I get my own campaign up and running 🙂 ) fit into any setting. Now, admittedly, there are some of the associated Paragon paths that require the Genasi, but I have no doubt that can be worked around by an enterprising DM (which I hope I am).

And thanks for the kudos, Martin, and for giving the Backgrounds section some coverage. Good to know it’s not cheese-worthy.

You love 4E and haven’t DM’d it yet?

Dude! Fun and easy DM’ing is the “killer app” of 4E!

Nice write up.