Today’s guest article is by Gnome Stew reader Rickard Elimää, and it details a fantastic technique for GMs: the “fish tank” model for creating a mystery adventure. Thanks, Rickard!

Why is a mystery like a fish tank? Imagine a fish tank with some piranhas in it. The tank and the water are the environment of the latent mystery waiting to be disturbed. The fish represent the people and their relationships with each other. Now imagine the GM throws the PCs into the tank, sits back and then enjoys the show. The players disturb the water and the fish react, revealing the problem or the mystery that the adventure is hung upon. The role of the players is to uncover all the relations so they can understand the adventure, and then it’s up to them how to solve the problem.

The fish tank can be used both for mysteries and intrigues but in this article I will just deal with creating the mystery. Once you get the hang of the technique behind the fish tank, you will be able to write an adventure in 20-40 minutes.

The Five Steps

So how should you write this kind of adventure? All you have to do is to follow five simple steps: create events, factions and relations; think of a storyline; and finally write key scenes.

1. Create Events

The first thing you have to do is create one or more events. What’s happened that will catch the players attention? What kind of event will pull the PCs into the story? You can create different kinds of events in the same adventure. Having only one event will give the adventure a clear goal. Two events give a more complex structure and three events will probably create a few parallel stories. I wouldn’t recommend having more than three events in an adventure because it would be hard to hold everything together.

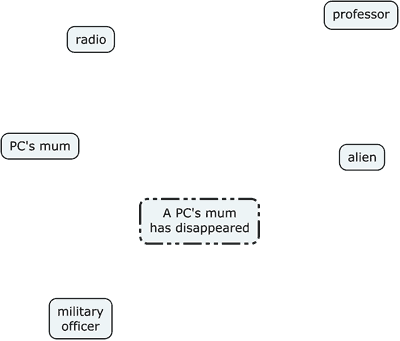

Take a clean A4 paper. Grab your pen and write one event in the middle of the paper. Let say that the mum of one of the PCs has disappeared. We don’t know why yet.

2. Create Factions

The second step is to create factions. Factions are persons, groups, events and items which the story will evolve around. Yes, events too. Factions are things that can move around or change their functions — what looks like a kidnapping (event) could really turn out to be something else. Places aren’t factions, because they can’t be moved around. Instead, they are locations where the scenes take place. In this step you should create at least three factions. Five is probably enough but you can make as many as 10-15 different factions for really complex adventures.

When you are about to create factions, think of things that you find cool, either from an RPG book or your imagination, and write them on the paper where you have already written the events. You can also look at the players’ character sheets. Is there anything there that you can use as a faction? Is the PC’s mum former military? Cool, let’s use that. Is one of the PCs interested in extraterrestrial life? Why not include that? Otherwise, you can always take inspiration from a movie that you’ve seen lately. Write anything that you can think of. Note that you still don’t have an adventure. You just have some random scribbles (Factions) on a piece of paper that you would like to feature in the mystery.

3. Create Relations

You are finally at the part where you actually create the scenario. Every line that you created is a relationship between two factions. Write on each line how the factions are connected. As you start describing all the relations a story is taking form. If you’re totally get stuck, don’t be afraid to erase the line and perhaps draw a new one somewhere else instead. When you are done, you will have a relationship map in front of you.

As you can see the professor only relates to two other factions in the adventure. This is a weak faction and you should consider drawing another relation to the professor, perhaps to the officer? Otherwise it may be that the professor doesn’t show up at all while you’re playing. Also try to take note of the faction that has the most relations to it. That one is going to be the most important and reoccur more frequently than the others. In this adventure, it’s the alien with six relations.

4. Think of a Storyline

Look at the relationship map that you have in front of you. Imagine the story behind what happened and what will happen. Obviously the alien escaped from the military officer and sought out the mum who helped him. Why? The mum has a radio that she got from a mission with the alien. They probably worked together with some goal. If you want, you can probably think about what kind of adventure the two were in. The mum knew that the military were going to find her and perhaps hurt her family so she chose to disappear. The alien’s mission is to escape Earth.

The military officer’s assignment is to get the alien back to the base before it escapes. He will go to any lengths to get the alien which in the end means that the alien will be captured and the mum liquidated. The professor will have picked up some strange transmission and after translating it, mistakes it for an alien assault. What she picked up was actually the alien signalling to the mother ship that he wanted to return.

This is what’s going to happen if the PC’s do not get involved. This is both the background and a little bit of the future. It’s important that you just imagine the storyline. Don’t write it down, because that will lock your thinking and perhaps force the entire story on the players.

5. Write Key Scenes

The creation of a scene is something that comes naturally in RPGs. Whenever the PCs are arriving at a new place or stays in on spot for a longer period of time, a new scene is created. A key scene reveals the factions in an adventure so the players can move on and find out the relations between them. Below are some examples of key scenes.

The PCs arrive at the mum’s house in the suburbs. Some children are playing, there are some cars on the street, one PC notices a white van with a satellite dish on its roof. It’s a sunny day in an otherwise sleepy neighbourhood. The mum’s house is locked and the first thing that strikes the PCs are that it’s really messy, like someone has searched the place. One person notices a framed photo of the mum in military outfit beside an officer. They are both smiling and the officer has his arms around the mum. Suddenly a loud shriek blasts from an otherwise normal-looking radio. The noise hurts the PCs’ ears. After a few seconds the shriek stops and is followed by a minute of gibberish. A while after the transmission, probably while the PCs examine the radio, they hear a voice coming through. “Hello, is anybody there?” It’s the professor in the white van outside. It’s a two-way communication radio disguised as a normal radio.

The professor wants to meet the PCs and have them bring her the radio. She’s reluctant to actually tell them what the radio is for, because who will believe her if she said it’s to do with an alien assault on Earth? Depending on how the PCs handle the situation she may talk, she may try to buy the radio. or she may give up and go to the military instead. The radio is linked to the alien’s own radio and by tracking the signal they can find out where the alien is located.

At some time, the military will show up to talk about the PC’s mum. It can be outside the PC’s apartment, during the talk with the professor, or just having the PC forced into a black van that stops beside them. The PC or the PCs will meet the military officer who wants information about the mum. He assures them that he only wants the best for the mum and that she could be in danger. The officer’s intent may be good, but orders from the top will make him remove mum from the action and return the alien.

How or if the PCs get here is up to them, depending on how they acted in previous scenes, but they end up at a calm lake where the alien wants to be picked up by a mother ship. Perhaps the army will show up, perhaps they are hunted by the army, perhaps they are helped by the officer that still loves the mum, perhaps the professor helps the PCs to the place but betrays them by bringing the army. The PCs will at least see the mum carrying an alien who is no bigger than an infant.

Working With The Fish Tank

The example above is a really short adventure, probably no longer than one session. If you want the game to last several sessions, involve more factions and more events. You can even do a fish tank inside a fish tank, or play this scenario as above and then take a few factions from it to create a new fish tank that is somewhat connected to the previous one.

The relationship map may look like chaos if you have around fifteen factions, but it’s easier to manage the map than it looks. The thing is that you only need to look at the map where the PCs are at the moment. Are they talking to the military officer? Look at the map to see which relations you can reveal.

The Two Phases

During game play, the players will go through two phases. This isn’t something you need to tell the players, but it’s good to keep it in mind. The first phase is exploration, where the PCs meet all the factions and find out the relations between them, mostly by interacting with them. The second phase is problem solving. So the players got all the pieces? What should they do with them? If they are convinced that there is an alien invasion going on, perhaps they will seek help from the military. If they do, how will they save the mum? So even if the PCs get all the pieces, it doesn’t have to be obvious what they should do.

Give Out All The Information

Don’t be afraid of letting the players know too much. Every time they interact with someone, give out a relationship as a reward and for every new scene, try to give them at least one new relation. If the players get stuck in the adventure, repeat the factions and their relations, either in-game by reporting to someone or by just discussing it with your players. You could also create new scenes where you give them more clues (read: reveal more relations). Discover the fun part of giving too much information to the players. Sure, you have your relationship map but the players need to create a logical map from the pieces you give them. The more pieces, the harder the puzzle is to solve.

Create A Drive

It’s important to always include a goal so that the players will take the initiative, and want to seek out new factions and interact with them. Create a drive, a goal, in the beginning of the adventure. Nothing will happen if the PCs are sitting in an inn, waiting for that mysterious stranger.

Afterword: I used CMapTools to create the relationship map, but I normally use pen and paper. I would like to thank Terry Regan and Craig Judd for helping me out improving this article.

Thanks for the article.

I created mysteries before but not using factions and relationships, it was less structured.

I usually forgot to provide enough information to the players or didn’t repeat it enough.

With a relationship map I have a more structured way to handle mysteries and giving out information.

Yeah, this looks like a tighter way of getting everything down so that there’s less ambiguity about the interactions between NPCs and factions.

I’ve been working on the plot for my latest game and can already see a couple of links that I hadn’t thought of, just by mentally picturing the relationships as you have shown them above. Thanks!

I used to use a similar method for my vampire games and my shadowrun games. For Vampire, I called it my social map, and built the PCs in there. I would use different styles on connecting lines to show things like an unknown connection (Officer loves Mother, but she has no idea), known (Officer loves Mother, she knows, but does not feel the same), and dfferent colors to have things like a positive or negative aspect to it (Red, solid line with love tag: Officer loves Mother, she knows, doesn’t feel the same. Officer is biter, and wants to ‘show her’) etc. It was a lot of fun to build these.

I expected to hate this article since as a DBA I have a long acquaintance with ER diagams, and over the years have perhaps over-used them in too many inappropriate ways outside of the purpose they were invented for, but I came away from reading this with a couple of useful new ideas for plotting my increasingly convoluted Delta green campaign so thank you this Guest Author. If I knew your name I would immortalize you as a villain in that campaign (probably an ironically short-lived villain, given the large amounts of lead handshakes with which my players are wont to greet suspicious strangers).

I do think that the technique should be paired with another when it comes to describing the scenes – the “fate-style” overview that lists important sensory impressions and cues along with key personnel c/w motivation notes, so that the scene is not so much a script as directors notes from which the GM can quickly remember and improvise upon the necessary points. In my opinion, naturally.

Of course, this “A4” heresy needs to be replaced with doctrinally-sound index cards before the technique can be truly approved of in these halls. 8oD

Unless a guest author requests anonymity (as yet, no one has), their name is always mentioned in the introduction. The author of this article is Rickard Elimää.

Well I’m also working and busy and blind as a bat. Hmm. That’s a great and evocative name too.

Tomorrow’s mission will undoubtedly involve going toe-to-toe with the dastardly Rickard Elimää, millionaire arms dealer and Mythos Wizard of the most virulent stripe.

I pity the poor buggers who attempt to take him on. I’m thinking a night raid on one of his factories, a stealthy bit of breaking and entering, some juicy secret-uncovering to do with fraudulent contracts and a locked steel door behind which sits a Shoggoth, somewhat annoyed after years of experiments (both mundane and magical) done on it in the name of science. How will it vent its spite I wonder?

Damn. Now I’m hungry.

Haha, I’m flattered. And it’s not that far from the truth. 😉

Very well put, Rickard. This is a great presentation on this type of prep. I end up using a similar system once my improvising has led me to a situation where I can no longer keep track of all the relationships in my head. I’m lazy that way.

I usually come up with personalities for my factions, and let the relationships develop through interaction between these personalities. I love to create characters to play so it’s the natural starting point for me, but I really should practice this sort of note-taking more. As you said, relationships are clues, and are much meatier plot-wise than interesting (at least to me) characters.

Come to think of it, this would be perfect for the supernatural mystery campaign I’m kicking off next week…

Cool that you all liked the article. Be sure to write here to tell about your success or what went wrong or if something troubles you on one of the steps in creating the fish tank. 🙂

Definitely helped me out I’m just starting my first design so this helps a lot.

I made a parlor game for a two page roleplaying game contest. You create a fish tank with that game, and it uses the same formula as described in the article. The event is Mr. Crow being murdered. The group then creates factions (people, events, and items), and during the rest of the game the group creates the relations.

Here is a link for the interested.

What I think is neat is that you can probably solo play that game to create a murder mystery for a roleplaying game session.