Featured image is of poet Edna St. Vincent Millay, sourced from The Poetry Foundation.

You can find the first part of this article posted here.

I’ve found myself more and more intrigued with single player roleplaying games. The Beast by AlekÂsanÂdra SonÂtowska and Kamil WÄ™grzynowÂicz is an unsettling erotic game for one player where you answer daily prompts in a journal, detailing a sordid relationship with a monster. A Real Game by Caitlynn Belle is an interrogation of body, self, and the idea of a Game that also includes introspection on prompts give as the game progresses. Even games that are meant to be played with others can be repurposed into a single player experience. Avery Alder’s The Quiet Year is a fascinating game about a community rebuilding after a devastating war. The game plays one “week” at a time with players answering prompts on drawn cards and then creating a shared map of the environment. I’ve been engaging in a fantastic reimagining of The Quiet Year as a solo experience, pulling one card at a time over the course of many, many weeks. You can hear the entire game on the podcast From The Jackals To The Shepherds if you are interested.Â

With all of these single player games using prompts as game mechanics the opportunity presents itself to create a mashup of play itself. Taken as written, the rules ask you to answer the prompts, with the assumption that you are composing your answers alone (or with others in a live environment like The Quiet Year). However, if you were interested in transforming this structure, I’d encourage you to look into Conceptual Writing, a genre adjacent to fanfiction. Conceptual Writing is interested in teasing apart our assumptions on ownership and authorship, how we frame and contextualize art, and where art does and does not belong. The specific approach I’ve found interesting recently is the capture, repurposing, and mashup of poetry and roleplaying games.

One of the Agendas, driving instructions to all players, of Monsterhearts, is to “Keep the story feral”. This is a piece of advice that I like to carry over into every game I play. Keeping it feral means that the fiction is alive, unpredictable. A story becomes feral because we can’t read our friends minds at the table, and the game encourages you to keep things messy, to recombine ideas, and to play off of each other, with the abrasions between everyone’s personal story drives producing the most interesting play. With that in mind it might seem difficult or impossible to have a feral single player game. You know everything in your own mind. At that point, is it feral play or is it fiction composition? By embracing conceptual writing techniques and repurposing text you create a single player experience in discovery writing that can get close to feral stories.

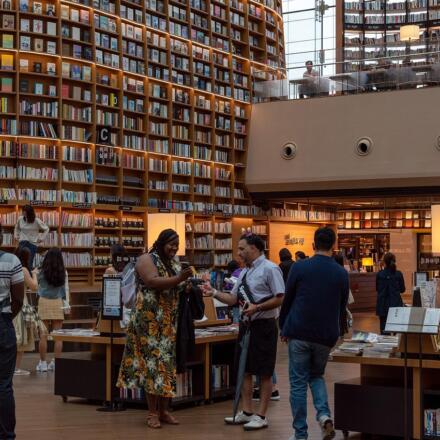

In my single player, year-long game of The Quiet Year, I had an idea one week. I would pull in quotes of poetry and weave them into the prose of my narration. It started as a way to flower up my descriptions, pulling natural imagery from the works of Wordsworth or Blake was a way to emphasize the pastoral image of a small community rebuilding. It became a way to develop plots, assign characters themes & motifs, and surprise even myself while writing. In one session, I pulled a poem called “Renascence”, by poet Edna St. Vincent Millay. I pulled the poem at first because of its natural imagery, the repetition of the phrase “three long mountains and a wood” perfect for the moody forest environment the community found itself. But the more I wove the poem into the prompt for the week, the more it took up the labor of moving the story forward. As the poem’s speaker narrated for me, I wove the verse and the events of the story into my journaling of that week’s prompt.

In “Renascence”, the poem’s speaker falls into a disturbing examination of the self & its position in the world. They confront immediacy and eternity, walking between life and death, sinking into the very earth itself. The underlying plot to this point had been trying to hide horrible forest spirits from the community, trying to navigate arcane rituals to prevent a cycle of destruction, keeping ourselves safe in our new environment. “Renascence” pushed all of those together, culminating in one of the recurring characters in the community finding herself above the world and apart from it, transcending into the forest itself and reincarnating with a terrible revelation.

Repurpose old pages, favorite passages, unread chapters

I had not read “Renascence” before starting to work it into my log for that week. I was caught off-guard by the new direction it had given my story. The poem had taken my story in its jaws, literally one hundred years after it had been published, and run feral with it into the woods. Edna St. Vincent Millay died in 1950 but she had become an integral part of my play. I had adapted and transformed her poem and her words had transformed my narrative.

Repurposing text is only one example of the various techniques under the umbrella of conceptual writing. Blackout poetry, where the poet takes a longer text and obscures portions, leaving the uncovered text to create something new, is another popular example. Constrained writing, where the author places rules on what may or may not be allowed in composition is another popular practice. I encourage you to play with existing text, re-examine some of your favorite poems or song lyrics, and create something new by engaging in past art in a way that changes how you see the art as well as impacting the games you play.

If you do, I want to hear all about it.